Flavour seeker creates community around wine, oysters and passion

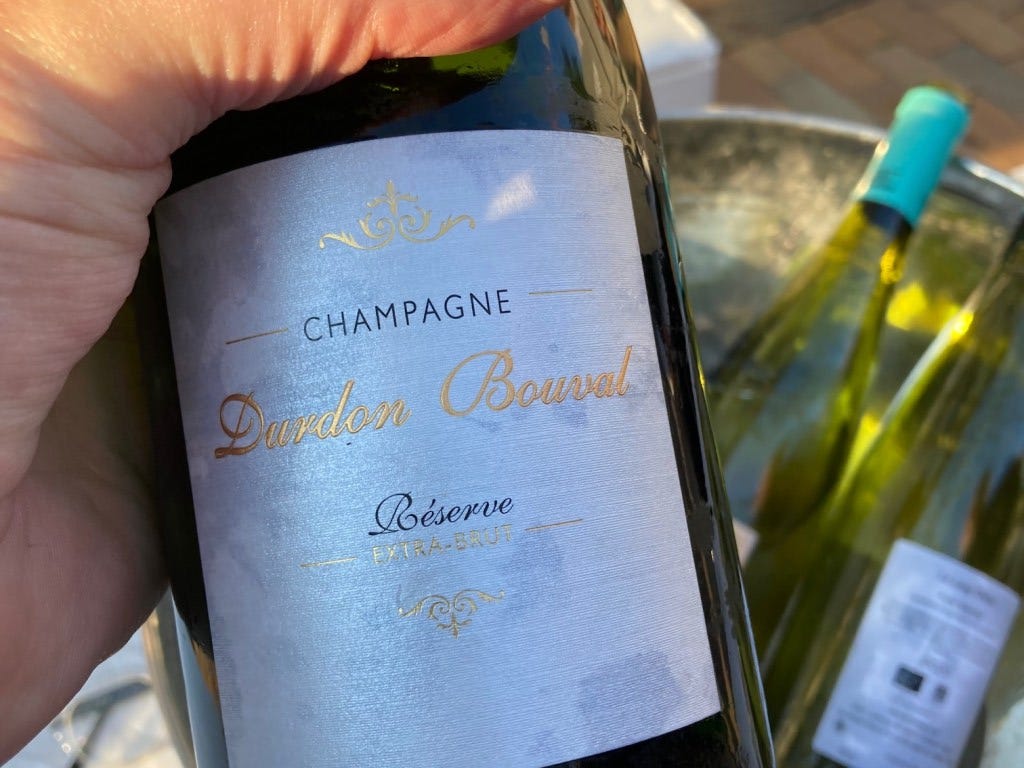

French expat and Copenhagen-based flavour seeker Victor Monchamp oozes enthusiasm; particularly about the route his life is taking him. As the charismatic owner of the Paris90 wine shop and bar Victor is building a community of likeminded people fascinated by wine, oysters and food pairings. He says he has been born twice. Once to his birth parents and secondly after meeting his Danish soulmate, and now wife, and creating Paris90; ‘home to our soul’, he says.

Victor focusses on natural wines from sourced from small and passionate winemakers, names noted in his enviable contacts book. He collaborates with Fiskerikajen, one of Denmark’s top oyster importers and offers many of the finest French oysters from people and companies such as Maison Gillardeau, the Roumégous family and their indispensable claires [oysters finished in knee-deep claires (rectangular salt ponds) for at least one month, during which they fatten up and take on a sweeter, fruitier flavour]. Joël Dupuch in Bassin d’Arcachon, Jean-Luc Le Gall in Brest.

Wine, oysters and culture at Paris90

Much of the life in Paris90 takes place around a huge table made from a fallen oak tree that had lived for some 250 years. Today it hosts tastings and events with a focus on wine and Victor’s other love, oysters. At other times, artists can hire the space to share their craft and insight in world, while organised cultural gatherings focus on timely issues such as ecology, the climate emergency and responsible consumption.

Merroir, a sense of place

I first met Victor on the streets of Tønder, a town in southern Denmark that was co-hosting the 2021 Danish Oyster Festival. He was setting up stall alongside an oyster shucker and chef (Jonas Harboe from Denmark’s Stammershalle Badehotel), and a beer seller.

Victor advocates merroir, the equivalent of wine’s terroir, as a way to understand the various nuanced flavour profiles of oysters, harvested from different waters giving the bivalves a sense of place through the various physical interactions the oysters experienced from sea water, currents, tides, temperature, algae, rainfall and season.

“Oysters are like wine, the taste and consistency depends on the oysters’ ‘merroir’, just as the taste of the grapes in a wine varies according to their ‘terroir’. A chardonnay tastes different whether it has its roots in California, Australia or France. Exactly the same is the case for oysters, which have different tastes and properties, whether they are from Normandy, Brittany, Ireland, Denmark or, for example, Japan,” says Victor.

Oyster Grand Prix

Victor’s main role during the week was to host the Oyster Grand Prix. It’s where the world’s best oysters judged and ranked on appearance and taste. This year the judging panel tasted eight different oysters from Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland, France, Italy, Portugal and Canada.

First place went this year to France and the oyster Speciale de Claire from Famille Roumégous, which impressed the jury with its beautiful appearance, green colour, intense taste and long aftertaste.

“It’s the sound of oysters is the first thing I remember. We were a big family, and the conversation went on at the dining table. But when oysters came on the table, conversation fell silent,” says Victor. Then you only heard the sound ‘mmmuuummm ..’ followed by ‘aaaahhhh ..’. It is an international language that everyone understands and fascinated me. Already as a 10-year-old I loved oyster parties (held during family holidays in France) because unlike sweets and ice cream, we were allowed to eat our fill. Oysters are the healthiest thing to eat because they are full of important minerals and vitamins,” says Victor, who initially studied biology.

Tides are strength training for oysters

Scandinavians have been eating oysters for thousands of years. This is evidenced by excavations of manure from the Stone Age. But there are oysters on all continents, says Victor. “There are over a hundred edible oyster varieties.

“Strong undercurrent and tides are crucial to how strong the muscle in the oyster becomes. When the oyster comes out of the water, it feels stressed and threatened and closes, therefore current and tide act as strength training for oysters. The more active it is, the stronger the oyster becomes, and the better the taste of umami. A strong muscle also means that the taste is better preserved if the oyster has to go on a longer journey to reach its customer. Producers in oyster-free areas often simulate tides by mechanically pulling their oysters out of the water.” says.

Pollution has reduced the number of habitats for wild oysters, and where farmed oysters are produced the ‘farmers or growers’ have little input.

“You cannot feed an oyster, nor can you protect it from enemies or vaccinate it against disease. But one can try to take good care of it,” says Victor. In Normandy, where the tide is very strong, producers, for example, turn their oysters at low tide and brush them free of algae and move them around so they do not bother each other. “They look after them as if they were our babies,” he adds.

Changing weather affects taste

If you collect a bucket of oysters at Rømø, for example, you get oyster shells in many sizes, says Victor. At some point, the oyster itself stops growing, but the shell continues to grow. “The size of an oyster testifies to its age and weight, but in areas with colder waters such as Canada, an oyster can take several years to reach a size where you can eat it due to the cooler sea.”

“The taste nuances are also very different. If it has rained a lot, the oysters become sweeter, whereas drought highlights the saltier notes. I usually say that when you open an oyster, you get a sea view,” says Victor.

Exhibition and competition

The Oyster Grand Prix at the Danish Oyster Festival is as much an exhibition of different oysters as an actual competition. Sometimes you most want oysters with a certain sweetness, where the taste stays in the mouth. In other situations, you are more inclined to oysters which are more salty with a relatively short-lived taste. We are different as human beings, and with the Oyster Grand Prix I want to open the eyes and taste buds of curious and interested people to the great diversity of oysters,” he says.

Judges at the Oyster Grand Prix assess the oysters according to various physical and sensory parameters, such as firmness – some are firm and taut while others are softer. They also assess the length of the flavour (how long it lasts in the mouth), its intensity, and the various degrees of saltiness and sweetness.

“Some customers say that an oyster feels like drowning in seawater. I feel, on the other hand, that I kiss the sea,” says Victor. Is it French romanticism against Danish realism or just an expression that we humans as oysters are different? I pay tribute to diversity”.

Click here for Victor’s and Paris90’s website.

Want to know more about eating oysters in Denmark. Click here.

For more about the Sønderjylland region, click here.

The post Flavour seeker creates community around wine, oysters and passion appeared first on The Lemon Grove.